I have spent years tracking how technological shifts quietly reshape societies long before the public notices their full impact, and artificial intelligence stands out as the most consequential labor force transformation of my lifetime. The impact of AI on jobs and human skills is no longer theoretical. It is unfolding across offices, factories, hospitals, and classrooms with uneven speed and visible consequences.

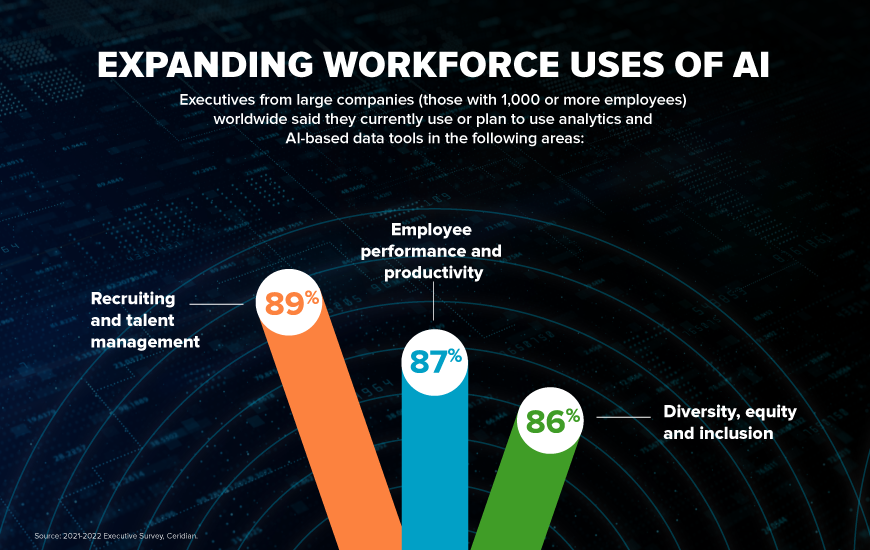

Within the first waves of adoption, AI systems began automating narrow tasks such as data entry, scheduling, and pattern recognition. Today, they assist with writing, software development, medical diagnostics, financial analysis, and hiring decisions. This shift is changing not just which jobs exist, but how work itself is structured and valued. In the first hundred words of this discussion, the core reality becomes clear. AI is not simply replacing tasks. It is redistributing human effort across cognitive, social, and strategic domains.

The central tension lies in whether societies adapt fast enough. While productivity gains accumulate for organizations, workers face uncertainty about relevance, wages, and skill longevity. Historical precedents from mechanization and digitization offer clues, yet AI differs in scope and speed. It encroaches on cognitive labor that once felt uniquely human.

As I analyze the economic signals and policy responses emerging globally, one pattern repeats. The future of work depends less on whether AI advances and more on how institutions guide reskilling, governance, and cultural expectations. Understanding the impact of AI on jobs and human skills requires looking beyond automation headlines and toward deeper structural change.

From Task Automation to Role Transformation

I often remind readers that jobs are bundles of tasks, not static identities. AI’s earliest workplace impact focused on repetitive and rules-based activities. Payroll processing, invoice matching, and basic customer support were among the first to change. Over time, AI systems expanded into semi-creative and analytical tasks, reshaping entire roles rather than eliminating them outright.

In consulting interviews I conducted in 2023, managers consistently described “role thinning” instead of job loss. Accountants spent less time reconciling spreadsheets and more time advising clients. Journalists used AI transcription and research tools to accelerate reporting while maintaining editorial judgment. This transition reflects a broader truth. AI alters the internal composition of jobs before it removes them.

The economic implication is significant. Workers who adapt to higher-value tasks gain leverage, while those confined to automatable functions face displacement risk. The challenge for labor markets lies in supporting this transition at scale rather than leaving adaptation to individual resilience alone.

Which Jobs Face the Highest Exposure

Not all occupations experience AI pressure equally. Exposure correlates strongly with task predictability and data availability. Clerical roles, routine manufacturing positions, and basic customer service functions remain highly vulnerable. In contrast, jobs requiring complex judgment, emotional intelligence, or physical dexterity in unstructured environments show greater resilience.

The table below summarizes relative exposure levels based on task characteristics observed across OECD labor studies.

| Job Category | AI Exposure Level | Primary Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Data entry clerks | High | Fully digitized, rule-based tasks |

| Manufacturing assemblers | Medium–High | Partial automation with robotics |

| Software developers | Medium | AI assists rather than replaces |

| Healthcare nurses | Low | Human care and situational judgment |

| Skilled trades | Low–Medium | Physical variability and context |

From my analysis, risk increases when institutions fail to create transition pathways. Automation alone does not cause unemployment. Policy inertia does.

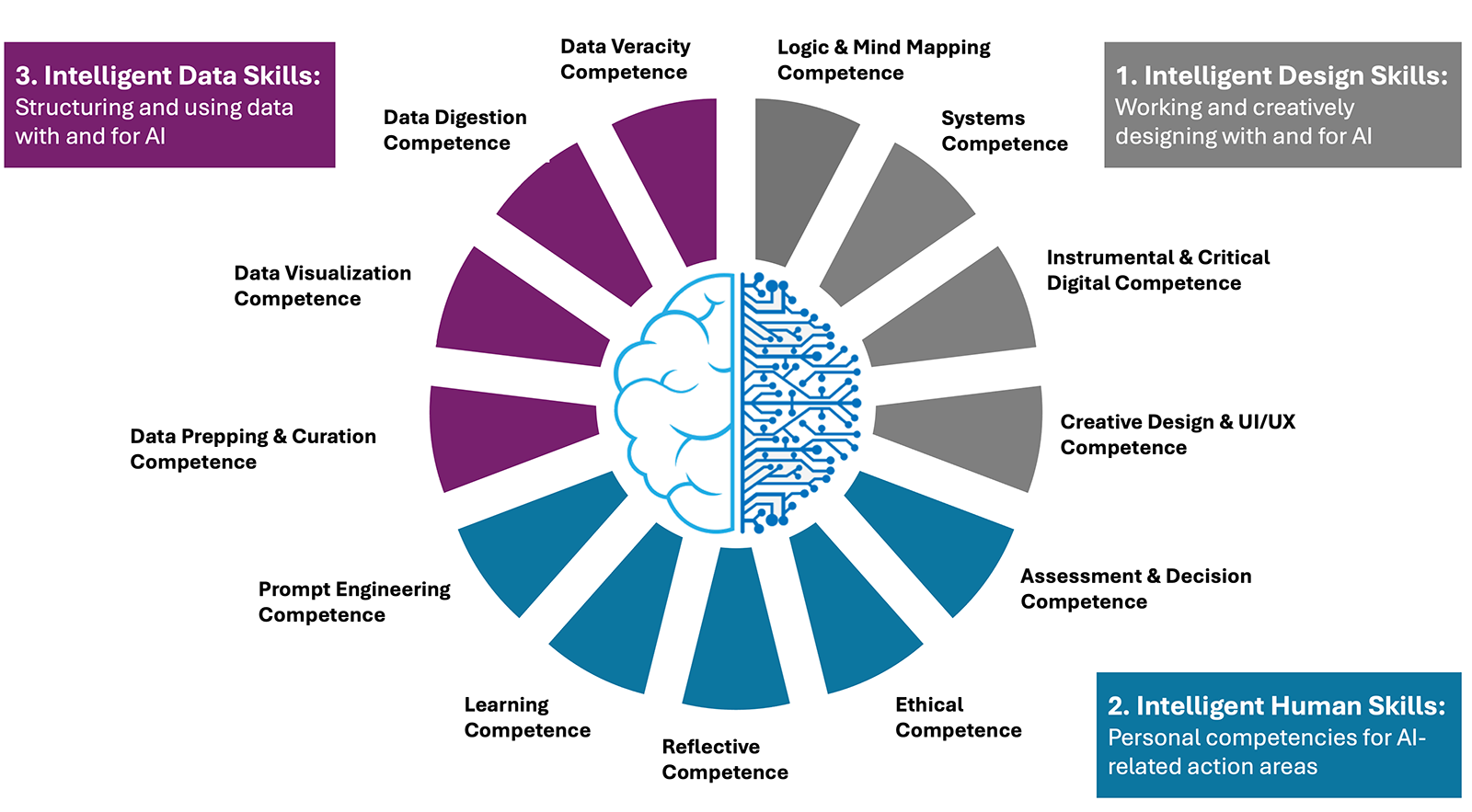

The Shifting Value of Human Skills

As AI absorbs technical repetition, human skills gain relative value. Creativity, ethical reasoning, collaboration, and systems thinking now sit at the center of economic relevance. This shift challenges traditional education models that emphasize memorization and standardized testing.

In workforce surveys conducted in 2024, employers consistently ranked critical thinking and communication above technical proficiency for long-term roles. AI systems can generate outputs, but humans remain responsible for framing questions, validating outcomes, and making normative decisions.

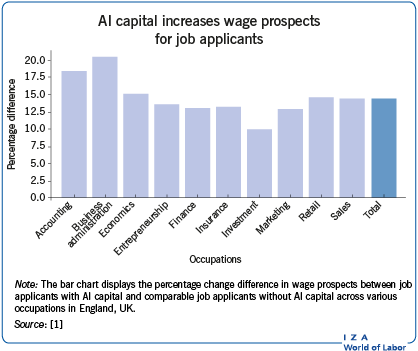

One economist I interviewed summarized it clearly. “AI raises the floor of technical competence while raising the ceiling for human judgment.” This insight aligns with my broader observation that future wages will increasingly reflect cognitive and social adaptability rather than narrow expertise.

Education Systems Under Pressure

Education systems sit at the fault line of this transition. Curricula designed for industrial-era stability struggle to keep pace with AI-driven change. Students still progress through linear pathways while labor markets demand continuous reinvention.

The timeline below highlights how educational priorities have shifted alongside technological change.

| Era | Dominant Skill Focus | Economic Context |

|---|---|---|

| 1950s–1970s | Manual and procedural skills | Industrial growth |

| 1980s–2000s | Digital literacy | Information economy |

| 2010s | Analytical and technical skills | Platform economy |

| 2020s–present | Adaptive, human-centered skills | AI-driven economy |

From my own experience advising education nonprofits, the most effective programs integrate AI literacy with ethics, collaboration, and lifelong learning models. The goal is not to compete with machines, but to work alongside them intelligently.

Productivity Gains and Unequal Distribution

AI delivers measurable productivity gains, yet distribution remains uneven. Firms that adopt early capture outsized benefits, while workers often see delayed wage growth. This imbalance fuels social anxiety and political tension.

Historical data from prior automation waves show a similar lag between productivity and wage alignment. However, AI accelerates concentration by favoring capital-intensive firms with data access and technical infrastructure. Without intervention, inequality risks deepening.

I have seen policy briefings where officials underestimate this gap. Productivity alone does not guarantee shared prosperity. Governance frameworks determine whether gains translate into broad-based economic security.

Governance, Regulation, and Labor Protection

Governments now face pressure to modernize labor protections. Traditional unemployment insurance and job classification systems struggle to address rapid task displacement. Forward-looking policies emphasize reskilling subsidies, portable benefits, and AI transparency requirements.

An international labor expert told me, “Regulation should slow harm, not innovation.” That balance defines effective governance. The most promising frameworks encourage responsible AI deployment while investing heavily in human capital.

Countries experimenting with lifelong learning accounts and public-private training partnerships show early signs of resilience. Delay, by contrast, compounds disruption.

Psychological and Cultural Impacts of AI Work

Beyond economics, AI reshapes how people perceive purpose and identity. Work remains a primary source of meaning for many adults. When roles change abruptly, anxiety and resistance often follow.

In interviews with mid-career professionals, I repeatedly heard concerns about relevance rather than income. People fear becoming obsolete more than underpaid. This psychological dimension demands attention from employers and policymakers alike.

Cultural narratives that frame AI as a collaborator rather than a rival reduce resistance. Language shapes adaptation.

The Long-Term Outlook for Employment

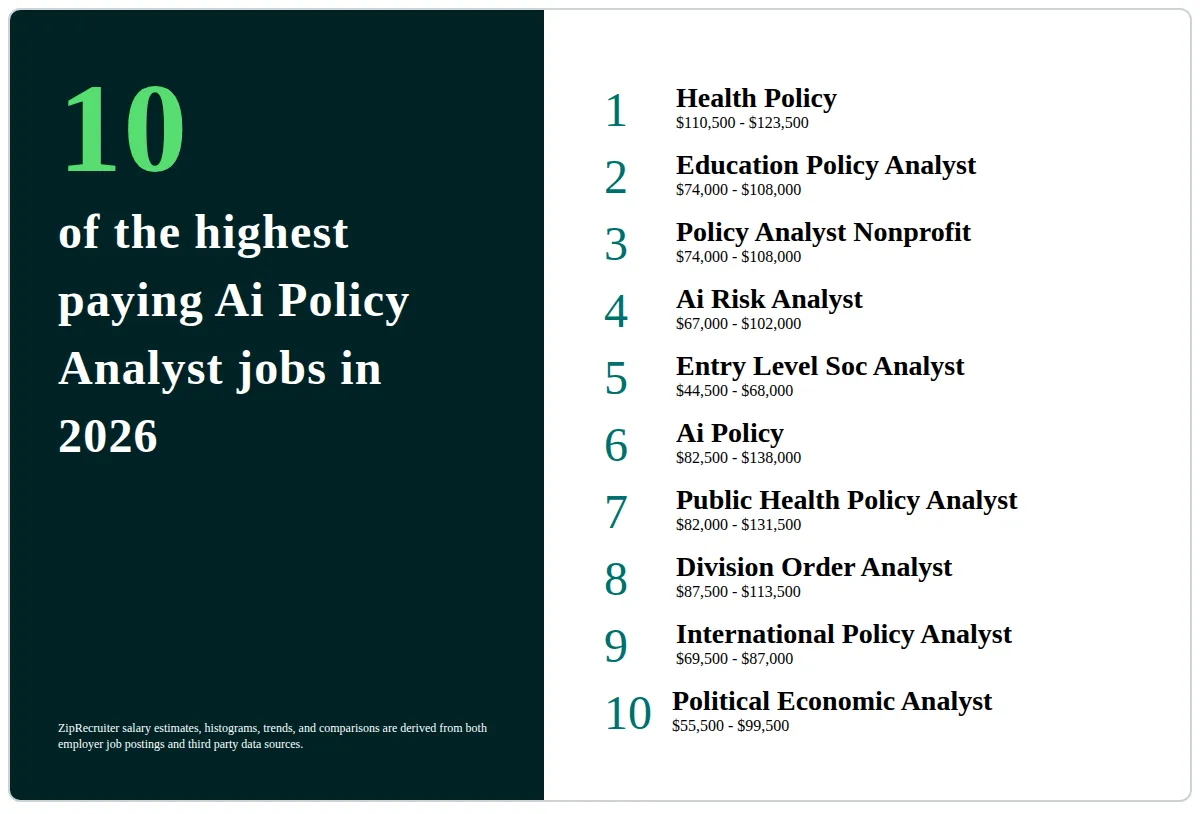

Looking ahead, most credible forecasts project net job transformation rather than mass unemployment. New roles emerge in AI oversight, ethics, data stewardship, and human-AI coordination. However, transition periods remain painful without structured support.

The impact of AI on jobs and human skills will likely mirror earlier technological shifts in one respect. Societies that invest early in people adapt more smoothly. Those that react late absorb greater social cost.

Takeaways

- AI transforms tasks before eliminating jobs

- Human judgment and adaptability grow in value

- Education systems must pivot toward lifelong learning

- Productivity gains require governance to ensure fairness

- Psychological impacts matter as much as economic ones

- Policy speed determines social stability

Conclusion

I view the AI labor transition as neither a crisis nor a cure-all. It represents a structural shift that tests institutional readiness and cultural flexibility. The impact of AI on jobs and human skills reveals a deeper question about how societies value human contribution when machines perform more work.

History suggests adaptation is possible, but not automatic. Investment in education, inclusive policy design, and ethical governance shape outcomes more than technological capability alone. As AI systems grow more capable, human skills do not diminish. They change form.

The coming decade will reward societies that treat AI as an amplifier of human potential rather than a replacement. The choices made now will define whether this transformation narrows opportunity or expands it.

Read: How AI Models May Evolve Over the Next Decade

FAQs

Will AI eliminate most jobs

AI is more likely to change jobs than eliminate them. Task automation reshapes roles, while new occupations emerge around oversight, coordination, and innovation.

Which skills are most future-proof

Critical thinking, communication, creativity, and ethical judgment remain difficult to automate and grow in value alongside AI.

How fast is AI changing labor markets

Change is uneven. Some sectors experience rapid shifts, while others adapt gradually depending on task structure and regulation.

Can education systems keep up

Only with reform. Lifelong learning models and flexible curricula show the strongest alignment with AI-driven change.

Is AI-driven unemployment inevitable

No. Outcomes depend on policy choices, reskilling investment, and inclusive economic planning.

References

Autor, D. (2015). Why are there still so many jobs? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 29(3), 3–30.

Brynjolfsson, E., & McAfee, A. (2017). Machine, Platform, Crowd. W.W. Norton.

OECD. (2023). Artificial intelligence and the future of work.

World Economic Forum. (2024). The Future of Jobs Report.