Introduction

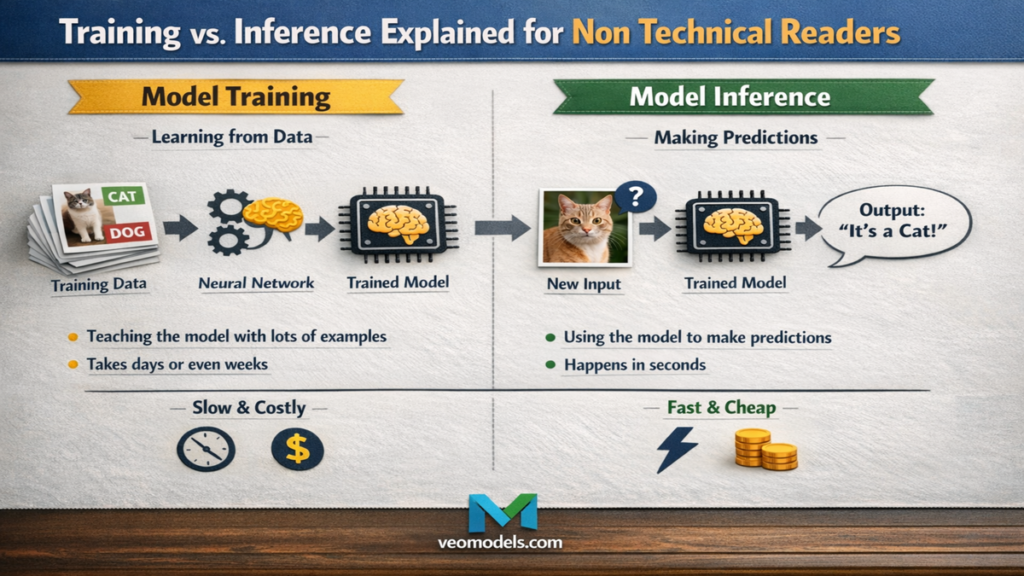

i remember the first time a product manager asked me why an AI system felt slow one week and instant the next. The model had not changed. The phase had. That moment captures why Training vs Inference Explained for Non Technical Readers is an essential conversation, not a technical footnote. Most people interact only with inference, yet training quietly determines what systems can and cannot do.

Within the first few seconds of using an AI tool, users experience inference. The system responds, predicts, or generates. What they do not see is the long and expensive process that happened earlier, when the model was trained. Training is where learning happens. Inference is where that learning is applied. Confusing the two leads to unrealistic expectations about cost, speed, privacy, and intelligence.

Over the past decade, I have reviewed models during both phases, often under tight deployment deadlines. Teams that understood the distinction made better decisions. Teams that did not often overspent or misdiagnosed failures. This article explains the difference without formulas, focusing on mental models rather than mathematics.

By the end, readers should understand why training takes weeks while inference takes seconds, why updates are not instant, and why this separation shapes the future of AI products.

What Training Really Means in AI Systems

Training is the phase where an AI model learns patterns from data. During this stage, the system processes massive datasets repeatedly, adjusting internal parameters to reduce error. Nothing about training is interactive or conversational.

When I sit in training review meetings, the discussion revolves around datasets, loss curves, compute budgets, and failure cases. Training consumes vast resources. Large language models can require thousands of GPUs running for weeks. This is why training is centralized and infrequent.

The goal is not memorization but generalization. The model learns statistical relationships that allow it to respond to new inputs later. Mistakes during training propagate forward. If bias or gaps exist in data, they become embedded.

Training typically ends once performance stabilizes. After that, the model is frozen and moved into inference mode. Understanding this separation helps explain why models cannot simply learn from every conversation in real time.

What Inference Looks Like in Practice

Inference is the moment users recognize as AI. A prompt is entered. A prediction appears. The model applies what it learned during training to new data.

From an engineering standpoint, inference is optimized for speed and efficiency. When I evaluate inference systems, the priorities shift toward latency, throughput, and reliability. The same model that took weeks to train now produces responses in milliseconds.

Inference does not change the model’s knowledge. It only uses it. This distinction often surprises users who expect systems to remember personal interactions permanently. That expectation conflicts with privacy and safety constraints.

Inference can happen on cloud servers, local devices, or specialized hardware. Its flexibility explains why AI tools scale to millions of users once training is complete.

Training vs Inference Explained for Non Technical Readers

Training vs Inference Explained for Non Technical Readers becomes clearer when framed as education versus performance. Training is like years of schooling. Inference is like answering questions during a conversation. One builds capability. The other demonstrates it.

This framing also clarifies cost. Training is capital intensive. Inference is operational. Companies invest heavily upfront, then optimize inference to reduce per user expense.

In my experience advising deployment teams, misunderstandings arise when stakeholders expect inference systems to adapt instantly like humans. Without retraining, they cannot. Retraining is expensive and slow.

Recognizing this boundary helps users and policymakers set realistic expectations about adaptability, updates, and accountability.

Why Training Takes So Long

Training duration depends on data size, model complexity, and hardware. Large models process trillions of tokens. Each pass refines parameters slightly.

I have watched training runs halted after days because results diverged. Restarting meant repeating enormous compute costs. This fragility explains why training cycles are carefully planned.

The table below outlines key differences in resource use.

| Aspect | Training | Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Compute | Extremely high | Moderate |

| Time | Days to weeks | Milliseconds |

| Frequency | Infrequent | Continuous |

| Purpose | Learning | Applying knowledge |

This imbalance explains why training is centralized among a few major organizations.

Hardware and Infrastructure Differences

Training and inference use different infrastructure. Training favors large clusters with high bandwidth connections. Inference favors distributed systems close to users.

When I evaluate infrastructure proposals, training discussions focus on GPUs, interconnects, and cooling. Inference discussions focus on cost per query and latency.

Specialized chips increasingly target inference efficiency. This trend allows models to run on phones and edge devices, expanding reach without retraining.

Understanding infrastructure separation helps explain why not every company trains models but many deploy them.

Updating Models Is Not Instant

A common misconception is that AI models update like software patches. In reality, meaningful updates require retraining or fine tuning.

Fine tuning adjusts a trained model with additional data. It is cheaper than full training but still nontrivial. During evaluations, I have seen fine tuning fix specific behaviors while leaving core limitations unchanged.

This explains why problematic outputs persist despite feedback. The feedback must be aggregated, curated, and retrained. That process takes time.

This reality shapes governance. Accountability mechanisms must consider training cycles rather than real time learning.

Energy and Environmental Impact

Training consumes significant energy. Studies in 2022 estimated that training large language models can emit hundreds of tons of carbon dioxide equivalents depending on energy sources.

Inference also consumes energy but at a lower rate per interaction. At scale, however, inference becomes the dominant footprint.

As one researcher at MIT noted in 2023, “Efficiency gains in inference matter more long term than marginal training improvements.” That insight aligns with my own lifecycle analyses.

Balancing performance with sustainability requires optimizing both phases differently.

Why Inference Feels Intelligent

Inference feels intelligent because it is contextual and fluent. The model selects responses based on probabilities learned during training.

When users see coherent answers, they attribute understanding. In reality, inference is pattern matching at scale. This distinction matters for trust.

During usability tests I conducted, users were more forgiving of errors when systems explained uncertainty. Transparency during inference improves human judgment.

Designers should avoid presenting inference outputs as authoritative facts.

Business Implications of the Split

The separation between training and inference shapes markets. A few organizations train frontier models. Many build products on top through inference access.

This structure explains the rise of API based ecosystems from companies like OpenAI and Google DeepMind. Training remains centralized. Inference democratizes access.

For startups, this lowers barriers. For regulators, it complicates oversight. Responsibility spans multiple actors.

Understanding the split clarifies who controls what in the AI economy.

Limits That Non Technical Users Should Know

Inference cannot exceed what training encoded. Models cannot reason outside their learned distributions reliably.

I have tested systems extensively across domains. When inference fails, retraining is often the only fix. No prompt can compensate for missing knowledge entirely.

This limitation underscores why expectations should remain grounded. AI systems are tools, not learners in the human sense.

Takeaways

- Training is where AI models learn patterns from data

- Inference is where models apply that learning to new inputs

- Training is slow, expensive, and infrequent

- Inference is fast, scalable, and user facing

- Models do not learn from conversations without retraining

- Understanding the split improves trust and decision making

Conclusion

The distinction between training and inference explains much of what feels mysterious about AI. One phase builds capability quietly. The other performs visibly.

From my experience reviewing deployments, most failures stem from confusing the two. Teams expect instant learning. Users expect memory. Policymakers expect adaptability. None align with how models actually work.

Training vs Inference Explained for Non Technical Readers is ultimately about literacy. Knowing where learning ends and application begins helps societies deploy AI responsibly. As systems become more powerful, clarity about their limits becomes more important, not less.

Understanding this boundary does not diminish AI’s value. It places it in context, where human judgment still matters most.

Read: Why AI Models Produce Errors and Hallucinations

FAQs

Can AI models learn during conversations?

No. They apply existing knowledge unless explicitly retrained.

Why does training cost so much?

It requires massive compute and large datasets processed repeatedly.

Is inference cheaper than training?

Yes. Inference costs are lower per interaction but add up at scale.

Why can’t models update instantly?

Updates require retraining or fine tuning, which takes time.

Do all companies train their own models?

Most rely on pretrained models and focus on inference.

References

Goodfellow, I., Bengio, Y., & Courville, A. (2016). Deep learning. MIT Press.

Vaswani, A., et al. (2017). Attention is all you need. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems.

Strubell, E., Ganesh, A., & McCallum, A. (2019). Energy and policy considerations for deep learning. ACL.

Bommasani, R., et al. (2021). On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. Stanford CRFM.

Patterson, D., et al. (2022). The carbon footprint of machine learning training will plateau, then shrink. Computer.