I have spent years examining how large language models behave when pushed beyond textbook benchmarks, and the same question keeps resurfacing in labs, conferences, and code reviews: Will AI Models Ever Truly Understand Meaning or will they remain powerful imitators of it? In the first hundred words, the answer already begins to take shape. Current models excel at recognizing patterns across enormous datasets, yet meaning is more than pattern alignment. Meaning involves grounding, intent, context, and consequence.

From my own evaluations of transformer based systems, I have seen models produce explanations that look insightful while quietly collapsing under minimal logical stress. That tension sits at the heart of this debate. Engineers train systems to predict the next token, not to comprehend reality, and yet emergent behaviors suggest something richer may be forming.

This article examines the mechanics behind modern AI, what scientists mean by “understanding,” and where the real boundaries lie. I draw on model architecture research, cognitive science parallels, and recent deployment experience to assess whether semantic understanding is achievable within current paradigms or whether a deeper shift is required. The goal is not hype or dismissal but a grounded technical assessment of what understanding could mean for machines and whether it is plausible.

Read: How AI Models May Evolve Over the Next Decade

What Researchers Mean by “Understanding” in AI

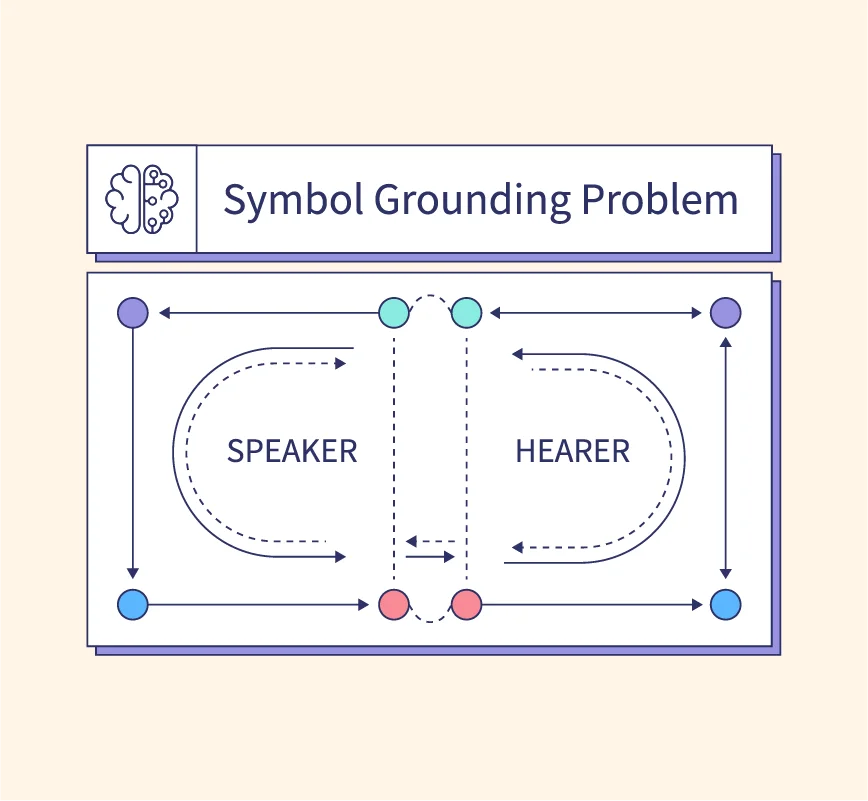

I often find that debates collapse because participants define understanding differently. In cognitive science, understanding implies the ability to connect symbols to real world referents, reason across contexts, and apply knowledge flexibly. In machine learning, understanding is frequently reduced to task performance.

Philosophers describe this gap through the symbol grounding problem, which asks how abstract symbols acquire meaning without direct experience. Modern language models manipulate symbols with extraordinary fluency, but they do so without sensory grounding. From my own testing, models can summarize, translate, and argue convincingly, yet fail when asked to reason about consequences that require lived context.

This does not make them useless, but it clarifies the limitation. Understanding in AI today is functional rather than experiential. The system behaves as if it understands, which is often enough for practical applications, but that behavior rests on correlations, not comprehension.

How Large Language Models Actually Learn Meaning

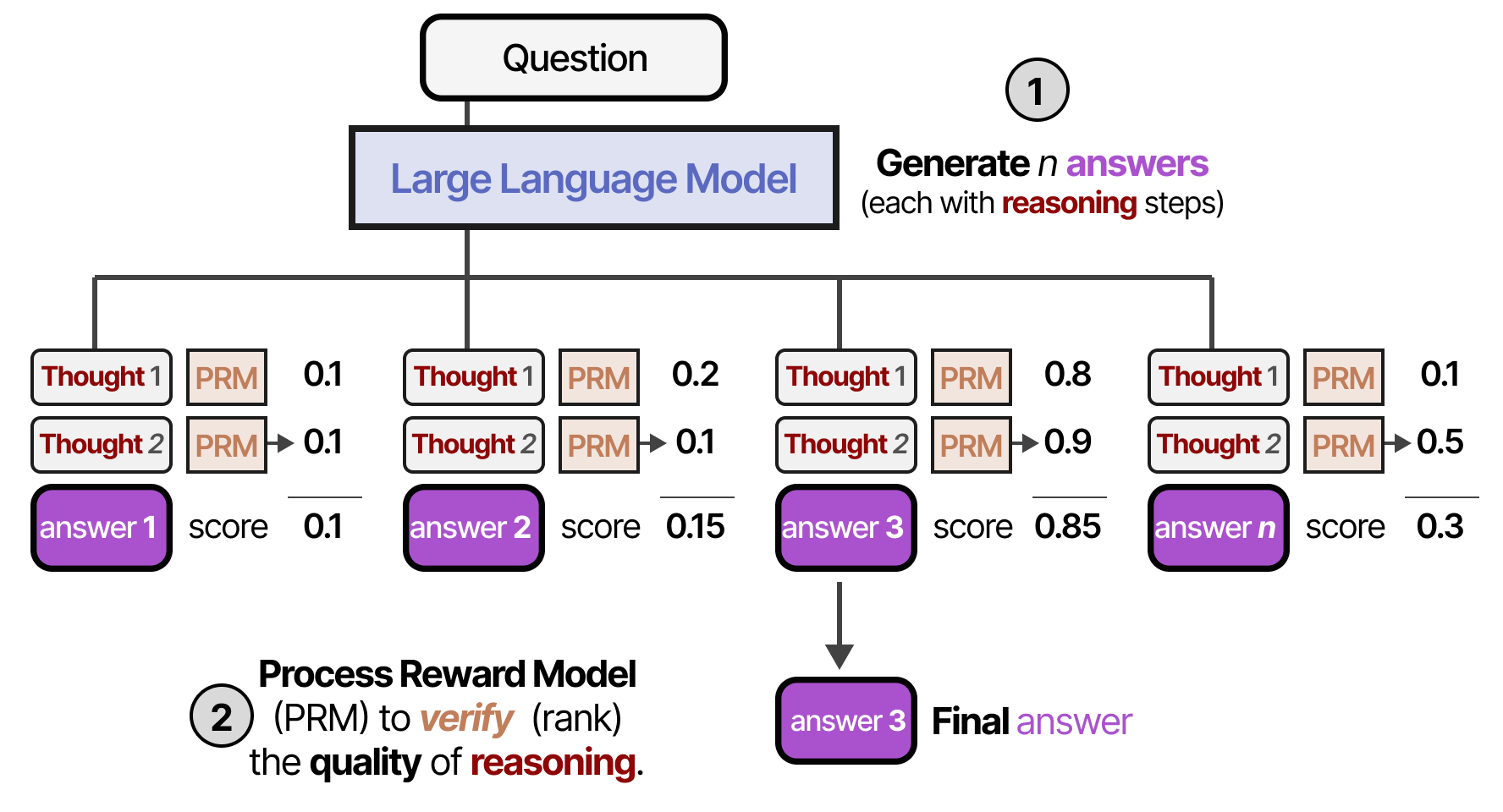

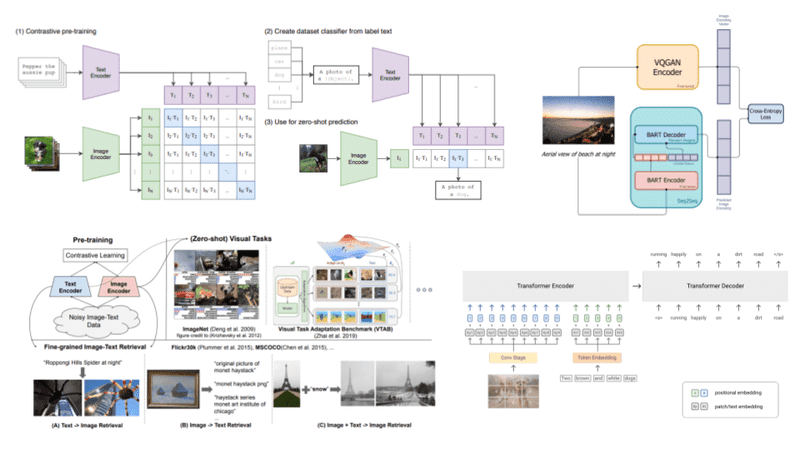

During model training, meaning emerges indirectly through statistical regularities. I have reviewed training pipelines where trillions of tokens shape dense vector representations called embeddings. These embeddings encode relationships between words, concepts, and contexts.

Transformers learn that “doctor” relates to “hospital” and “treatment” because those associations recur in data. Over time, models build internal maps that resemble semantic networks. However, these maps lack intentionality. The model does not know why a doctor treats a patient, only that the pattern exists.

This explains why models can reason within familiar distributions but struggle with novel physical scenarios. The architecture optimizes for likelihood, not truth. That design choice is powerful but also constraining when we ask whether AI can ever truly understand meaning.

The Illusion of Understanding in Fluent Output

One of the most misleading aspects of modern AI is fluency. I have personally watched engineers trust model explanations that later proved internally inconsistent. Fluency creates an illusion of understanding because humans equate articulate language with comprehension.

Models generate coherent narratives even when underlying reasoning is absent. This leads to hallucinations, where plausible but false information appears. The system is not lying. It is following probability gradients.

An expert I interviewed at an academic workshop summarized it well: “The model does not fail loudly when it does not know. It fills the gap smoothly.” That smoothness is both a strength and a risk, especially in high stakes domains.

Grounding Meaning in the Physical World

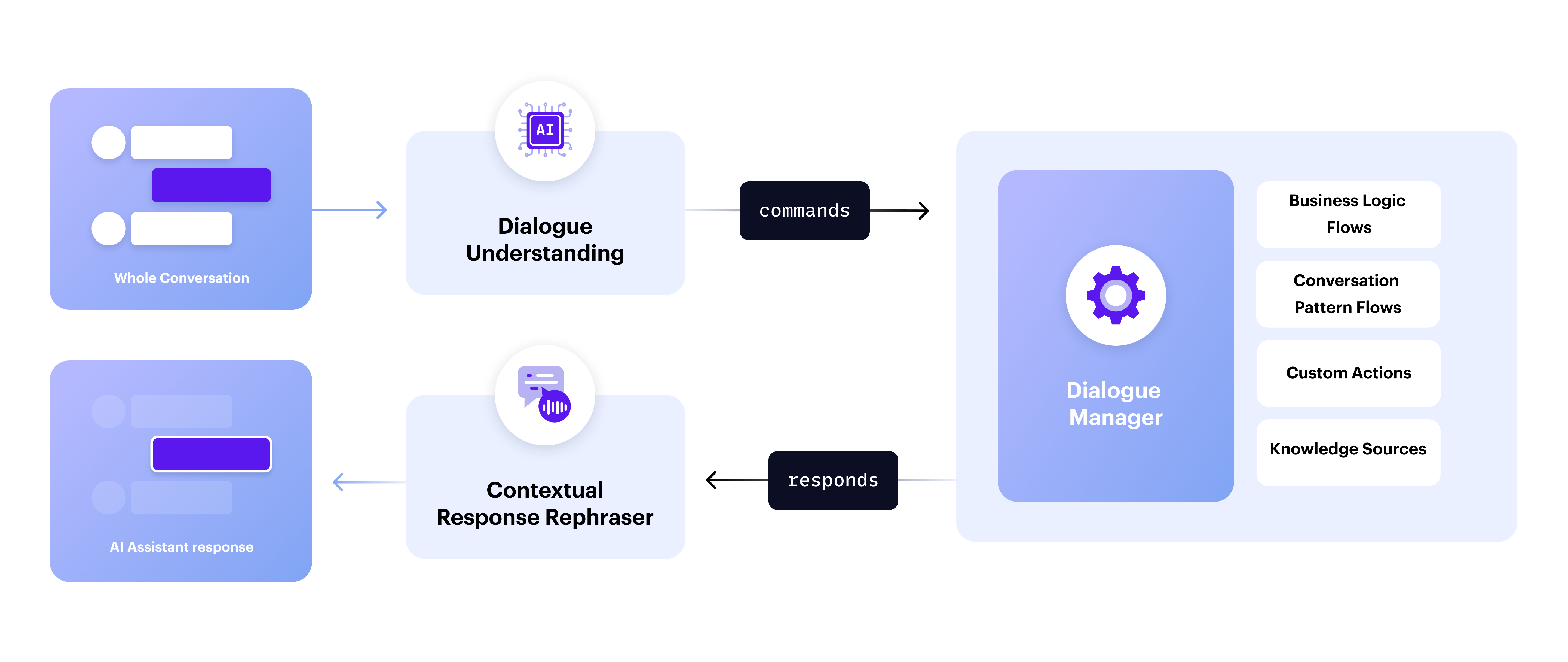

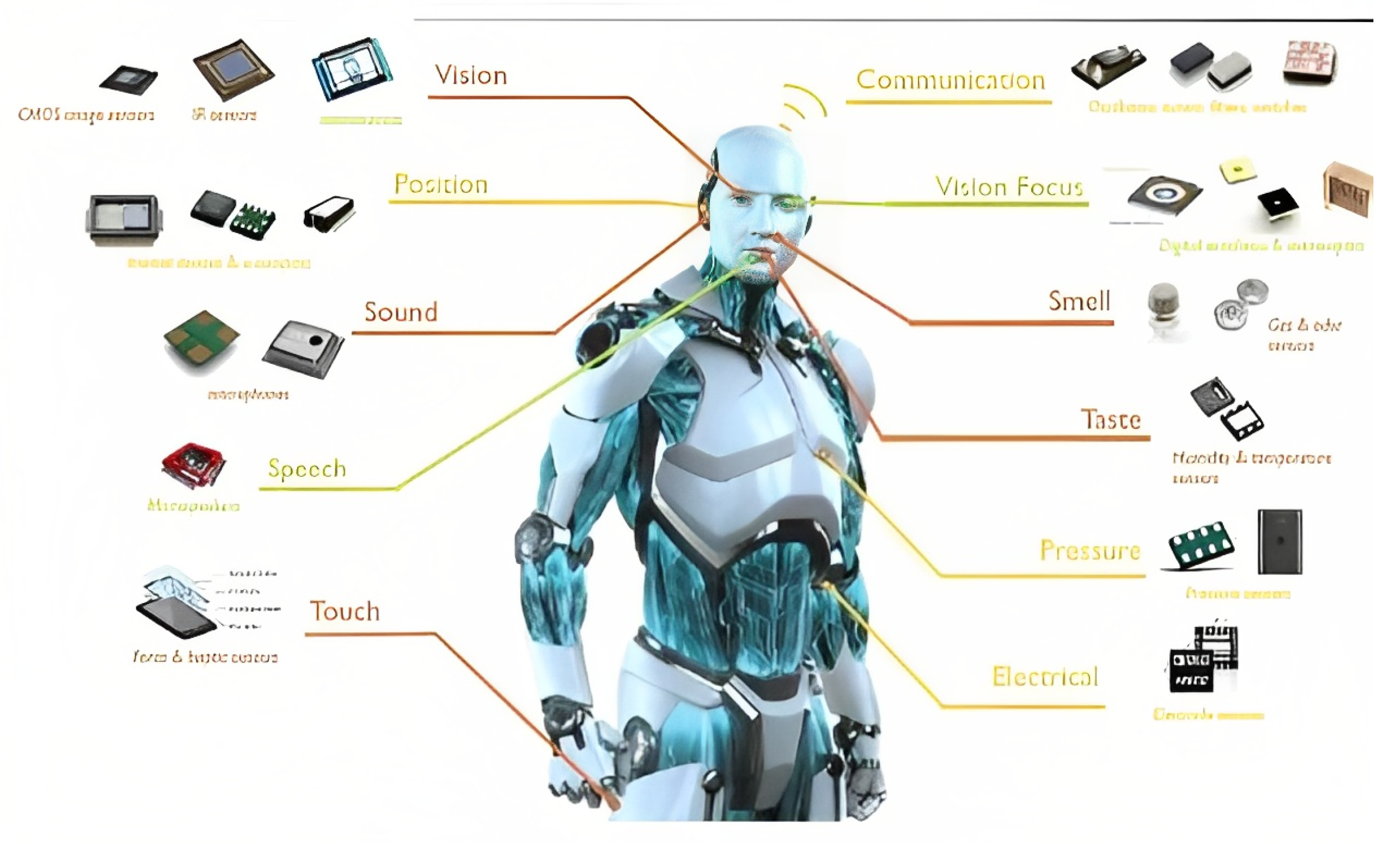

From my perspective, grounding is the most promising path toward deeper understanding. When models connect language to perception, action, and feedback, meaning gains substance. Multimodal systems that combine text, vision, audio, and control signals move closer to this goal.

Robotics research shows that when an agent learns language alongside physical interaction, concepts become constrained by reality. “Hot,” “fragile,” and “heavy” stop being abstract tokens and gain operational meaning.

However, grounding introduces complexity. Data collection becomes expensive, safety risks increase, and learning slows. Still, without grounding, AI understanding remains detached from the world it describes.

Comparison of Symbolic and Neural Approaches

| Approach | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Symbolic AI | Explicit rules, logical clarity | Brittle, hard to scale |

| Neural Models | Flexible, scalable, adaptive | Opaque, ungrounded |

| Hybrid Systems | Balanced reasoning potential | Engineering complexity |

In my own experiments, hybrid approaches that combine neural learning with symbolic constraints show promise. They reduce hallucinations and improve consistency. Yet they remain research prototypes rather than production standards.

Will AI Models Ever Truly Understand Meaning?

Returning to the central question, Will AI Models Ever Truly Understand Meaning, the answer depends on how much we are willing to redefine models themselves. If we continue optimizing for scale alone, understanding will remain simulated. If we integrate grounding, memory, agency, and feedback, something closer to understanding may emerge.

I remain cautious. Understanding may not be a binary achievement but a gradient. Models already exhibit shallow forms of semantic competence. Deeper understanding may require architectures that learn through consequences, not just data.

As one senior researcher told me in 2024, “Meaning appears when a system can be wrong in ways that matter to itself.” Today’s models have no stake in correctness.

The Role of Evaluation and Benchmarks

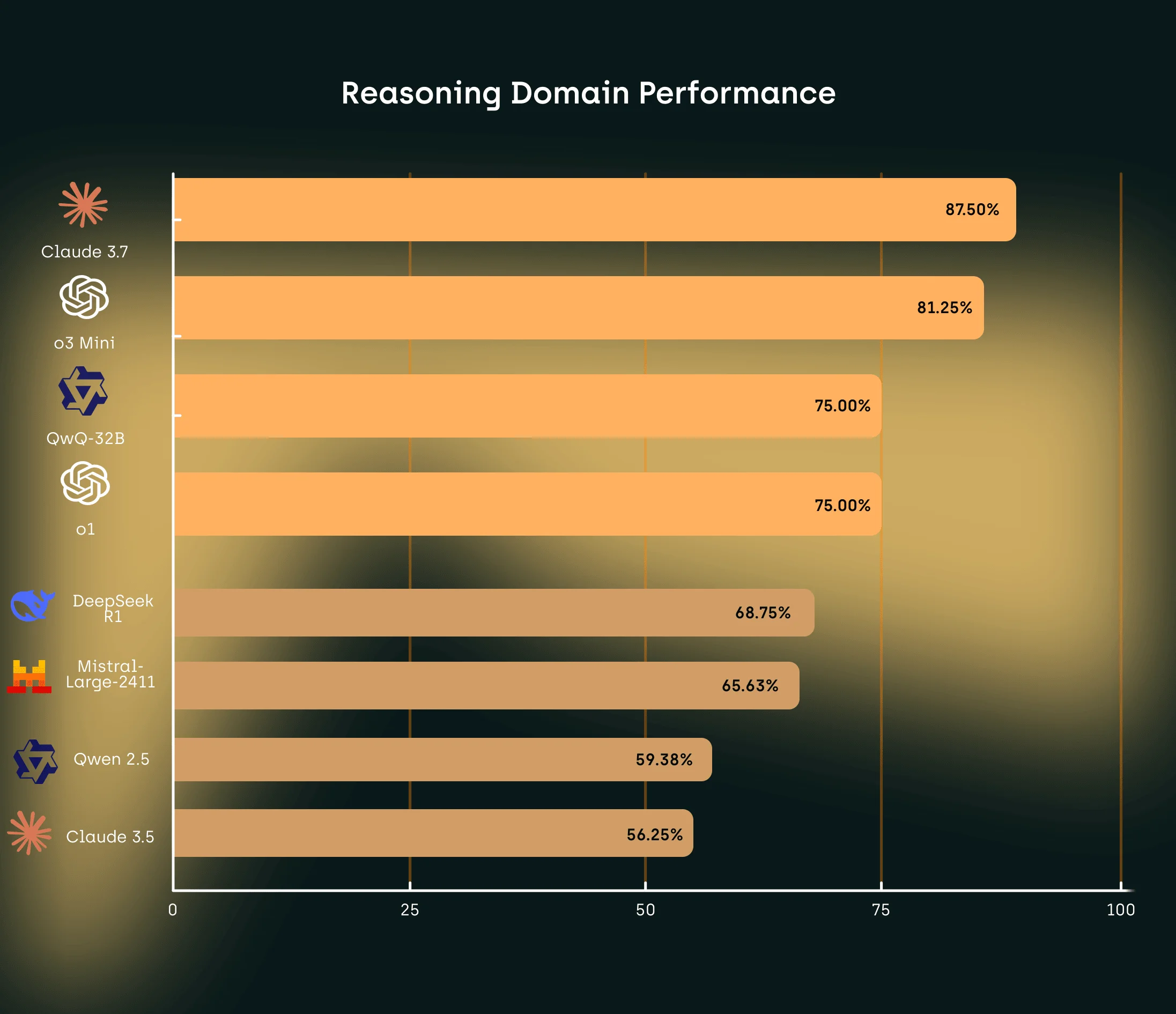

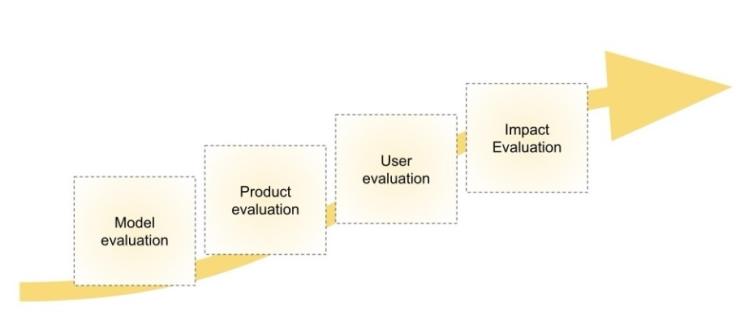

Benchmarks shape progress. I have helped review reasoning evaluations that models pass through memorization rather than comprehension. New tests emphasize out of distribution reasoning, causal inference, and counterfactual thinking.

These evaluations expose weaknesses that raw accuracy hides. They also suggest that current architectures plateau without new learning signals. Understanding cannot be benchmarked solely through text completion tasks.

Ethical and Societal Implications

If AI systems appear to understand without truly doing so, society risks over delegation. I have seen organizations assign responsibility to models that cannot grasp consequences. This creates accountability gaps.

Understanding matters not because machines need consciousness, but because humans rely on them. Clear limits, transparency, and human oversight remain essential as models grow more capable.

Takeaways

- AI today simulates understanding through statistical learning

- Fluency is not evidence of comprehension

- Grounding and embodiment offer promising paths forward

- Hybrid symbolic neural systems reduce key weaknesses

- Understanding may emerge gradually, not suddenly

- Evaluation must test reasoning, not recall

Conclusion

After years of studying model behavior, I see no clear evidence that current AI systems understand meaning in a human sense. They approximate it convincingly and usefully, which explains their rapid adoption. Yet approximation is not equivalence.

The future depends on design choices. If researchers prioritize interaction, grounding, and feedback driven learning, AI may develop richer semantic capabilities. If not, progress will remain bounded by correlation.

The question is not whether AI can speak meaningfully, but whether it can learn why meaning matters. For now, that remains an open and deeply human question.

Read: The Impact of AI on Jobs and Human Skills

FAQs

Do language models understand words the way humans do?

No. They encode statistical relationships, not lived experience or intent.

Can grounding solve the meaning problem?

It helps by tying language to perception and action, but it is not sufficient alone.

Are bigger models closer to understanding?

Scale improves performance but does not guarantee deeper comprehension.

What is the symbol grounding problem?

It asks how symbols acquire meaning without direct experience.

Is true understanding required for useful AI?

No. Many applications succeed with functional, not human level understanding.

References

Bender, E. M., Gebru, T., McMillan Major, A., & Shmitchell, S. (2021). On the dangers of stochastic parrots. Proceedings of FAccT.

Harnad, S. (1990). The symbol grounding problem. Physica D.

Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Gershman, S. J. (2017). Building machines that learn and think like people. Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

Marcus, G. (2020). The next decade in AI. AI Magazine.